In the light—or rather, in the shadow—of the growing threats of nuclear war, the activation of new global crisis zones, and the militarization of popular culture and public discourse, it is worth recalling that similar challenges, in different political constellations, were once met in entirely different ways. The second half of the last century was defined by the bloc division of the world, in which the rivalry between the U.S.-led NATO alliance and the Warsaw Pact under the leadership of the USSR fortunately never culminated in a full-scale armed conflict. Yet, war was waged by other means—through propaganda and counterpropaganda, trade restrictions, espionage, and technological, scientific, and other forms of competition. Many of these methods remain present even in today’s context.

In contrast to its position today, Croatia—then part of the former state—could once boast of far greater geopolitical relevance. Although this experience is not so distant in the past, it seems to have been largely forgotten in Croatian public discourse. Moreover, Yugoslavia’s 1948 “NO” to Stalin has been reduced to a minor episode within a generally suppressed history. The policy of non-alignment is mentioned only symbolically in school programs, and it is therefore unsurprising that its direct impact on social reality is scarcely discussed at all.

For generations who came of age in the 1990s and after, events such as the 1955 Bandung Conference in Indonesia remain largely unknown. The articulated need to end colonialism, racial divisions, and global bipolarity remains largely unknown, equally as in the context of the Brijuni Islands meeting between Yugoslav president Josip Broz Tito, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, and Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, or the First Conference of Heads of State or Government of the 25 Non-Aligned countries held in Belgrade in 1961. Although the Non-Aligned Movement has since lost much of its significance worldwide, Croatia officially continues to hold observer status to this day.

Non-alignment was not merely a matter of foreign policy, but also of cultural, economic, and trade diplomacy. This is where the exchange of people played a crucial role—Yugoslav workers and experts were systematically sent to Non-Aligned countries, while students from those countries came to Yugoslavia in turn. It is precisely this student legacy of the Non-Aligned doctrine that curator, artist, and activist Petra Matić has been studying intensively since 2019. Two years ago, she organized an exhibition at Zagreb’s Galerija VN titled Non-Aligned Zagreb. In the meantime, her research on the International Student Friendship Club (MSKP)—founded in 1962 by students from Non-Aligned countries—has developed into the Non-Aligned Archive, a project by the cultural association Jutro, featuring an expanding body of documentation on the club’s intercultural activities.

The Archive is founded on the principle of digitizing materials and returning them to their rightful owners, which is how stored objects and the knowledge associated with them become accessible to everyone. In May of this year, a series of the association’s activities helped raise the initiative’s visibility and highlight the history it chronicles. Among the Archive’s holdings, one can view photographs of the everyday life of students from Non-Aligned countries in Yugoslavia, reproductions of artworks by intercultural artists, documents from the Croatian–Latin American and Iberian Center (HLAIO) and the aforementioned MSKP, as well as issues of the newsletter Solidarnost, which the club published from 1966 onward. According to previous interviews Matić has given to the media, Solidarnost was the club’s only permanent publication of its kind and is considered the first Croatian magazine on international relations.

At the beginning of May, the Serbian Cultural Center hosted screenings of Aleš Verbič’s Slovenec po izbiri (2019) and Christian Guerematchi’s Blaq Tito (2022). Verbič’s documentary traces the life paths of several former African, Asian, and American students who came to Slovenia in the 1970s and 1980s, and have remained there ever since. Guerematchi, a native of Maribor with Central African roots, stages the hypothetical arrival of a “Black Tito,” unfolding somewhere between reality and dream, or the concept’s figuration and abstraction.

After the screenings, a discussion on the achievements of cultural exchange between Yugoslavia and other Non-Aligned countries was held with Mohamed Al Younis, a Jordanian who came to study in Croatia in 1971, and Rea Drvar, a younger-generation cultural anthropologist and museologist of partly Latin American descent. Their perspectives intertwined the broader history of cultural exchange among Non-Aligned countries with the personal stories of the participants, which were directly shaped by that history. As Al Younis emphasized, Yugoslavia experienced significant liberalization following the removal of Aleksandar Ranković from all his positions. This shift opened the country to an increasing number of Arab students, supported by the governments of their home countries. Drvar noted that Latin American students were perceived as less exotic in the local context because they were compared to Italians—or even identified with them.

Ultimately, based in part on the film material, it is possible to conclude that Slovenia stands out as an exceptional example of the successful integration of immigrant populations, whereas in Croatia diversity is still met with skepticism—even when it concerns minorities that have long been part of local society, such as the Roma. Even today, many years since the Non-Aligned university connections broke down, it is significantly easier for students from third (non-EU) countries to study in Serbia or Slovenia than in Croatia. Considerable bureaucracy in Croatia’s higher education remains a significant obstacle.

Within a span of a few days, Matić also held a video conference with African colleagues working on archives and the preservation of cultural heritage. The discussion, which was recorded and is publicly accessible, included Zainab Gaafar, a Sudanese architect and curator (Safeguarding Sudan’s Living Heritage), Mutanu Kyany’a, head of the digital collection African Digital Heritage, and Seth Avusuglo, representing the Ghanaian institution Library of Africa and the African Diaspora. This simultaneous virtual inauguration of the Non-Aligned Archive served as a professional exchange, during which each participant explained their approach to preservation and, perhaps even more importantly, to the contextualization of culturally marginalized heritage on a global scale.

Another of the May events initiated by Jutro was a collective reading at the Multimedia Institute in Zagreb with the British sociologist Paul Stubbs, who has lived and worked in Zagreb since the 1990s. The discussion highlighted Tito’s interpretation of the Non-Aligned policy and of the very foundations of Yugoslav statehood after the Second World War, as articulated in his 1954 address to the Indian Parliament. In addition to reaffirming the view of capitalism as a temporary stage to be surpassed by democratic socialism, Tito elaborated on the official position regarding the United Nations’ role in maintaining global peace, and on how Non-Aligned countries could complement those efforts. The policy of non-alignment was presented as a framework that enabled national independence, prevented further bloc divisions that could easily lead to conflict, and protected smaller nations from being absorbed by larger ones. This foreign-policy program is examined from a more distant historical and geographical vantage point in the 1987 text The Black Community and the Non-Aligned Movement, in which Barbara Lee analyses what non-alignment meant for the African American community in the United States.

The guided tour led by translator and linguistics PhD candidate Nawar Ghanim Murad extended the discussion on Croatia’s openness to communities with which the country no longer maintains cultural or other ties. Murad came to Croatia from his native Iraq in 2011. Unlike the young people who followed a similar path in the 1960s, 1970s, or 1980s, he encountered no structural support in his integration.

Had he been a student in those decades, he might have received one of the rare and generous Iraqi scholarships, which at the time could exceed 1,500 US dollars, or at least the modest monthly assistance of around 300 dollars. In any case, the Non-Aligned countries that sent students to Yugoslavia supported them with at least symbolic sums. In turn, these students were a living investment, set to become diplomats in the future. As Murad explained, Yugoslavia itself invested significant resources in educating new students in Yugoslav historical and political experience, which they could eventually bring back to their home societies. They could also help disseminate the desired image of Yugoslavia internationally.

Murad walked the participants through the Non-Aligned Zagreb, highlighting sites that were once significant for students from Non-Aligned countries. He brought to life locations such as the main railway station, the central post office, the space of today’s Importanne Gallery, Tomislavac Park, the Esplanade Hotel with its former bar Zlatni lavovi (Golden Lions), later Dijamant (Diamond), the State Archives building (once the city’s main library), the Botanical Garden, and other sites important along the everyday routes of the youth who have since enriched and contributed to Croatian society. The MSKP headquarters was located at Tvrtkova Street 5, from where it was temporarily moved to the N Pavilion of the Student Center in 1975. Following the 1990s war, the French Pavilion was considered as a new space for the club. However, as the pavilion was unsuitable and poorly maintained for such a function, the students demanded an alternative. They were eventually given only part of the building, which no longer exists in its original form. The club permanently ceased operations around the same time, when its premises were set on fire and its collections confiscated.

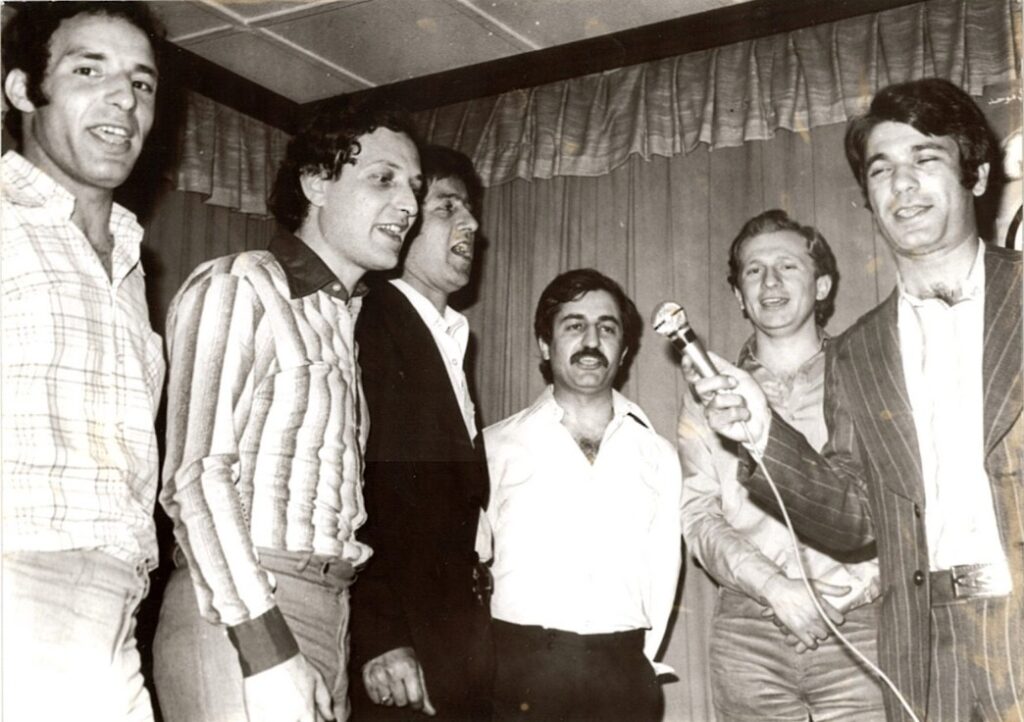

In its golden years, the activities of the MSKP were truly numerous. Foreign students independently organized courses in Arabic and other languages, film programs, presentations of national dances and other forms of intangible culture, and even blood donation drives. They helped new members secure rooms in student dormitories, obtain theater tickets, participate in national holiday and anniversary celebrations of foreign states, and later represent these countries in institutions and the industrial sector. The club guided future professionals within the systems they had a real chance to enter, a practice that stands in stark contrast to today’s experiences of entering the labor market, even for domestic students. Thousands of foreign students passed through Zagreb in this way, and many remained in Croatia. At the same time, around 14,000 Croatian workers went specifically to Iraq, many of whom built entire houses and comfortably supported their families back at home.

Jutro’s extensive, curatorially inventive program sustains the memory of international collaborations that nurtured curiosity toward different cultures and contexts, offering opportunities for mutual learning. Despite the post-1990s tendency to flatten the previous century into narratives of oppression and unfreedom, Jutro’s approach to the Non-Aligned heritage demonstrates that Zagreb’s cultural life has a far richer history than contemporary accounts typically acknowledge. The same holds for other major cities of the former Yugoslavia where similar student clubs once existed. Such a continuity of structural support, with the ultimate and tangible goal in the concrete improvement of the community, should be a source of collective pride rather than a story left to fade.

Once again, in a moment of intense geopolitical upheaval, the value of such initiatives lies in reminding society that the world—and one’s position within it—can indeed be conceived differently. Alternatives for how things might function do exist and have existed, and at times they have opened real space for collective resistence to an otherwise undesired reality.