Arsenie. An Amazing Afterlife (Alexandru Solomon, 2023)

If one looks up Father Arsenie Boca online, captivating stories emerge. A Romanian priest, theologian, mystic and artist who ultimately became an abbot, Boca is widely regarded as one of the most influential Orthodox Christian clerics of the 20th century. His life story has come to symbolize a redemptive lesson for Romania’s totalitarian past. Born in 1910, Boca was a gifted student who quickly rose through religious ranks. He was also an accomplished painter and translator of Greek texts into Romanian. Historical records suggest he was connected to the Legionary Movement in the late 1930s, a fascist, ultra-nationalist, anti-Semitic organization that seized power in Romania in 1940 under the decree of King Michael I. The National Legionary State led by the Conducător (“leader”) Ion Antonescu collapsed in 1941, just five months after its formation. Following the Communist takeover, Boca was arrested for the first time–a prelude to years of surveillance by the secret police.

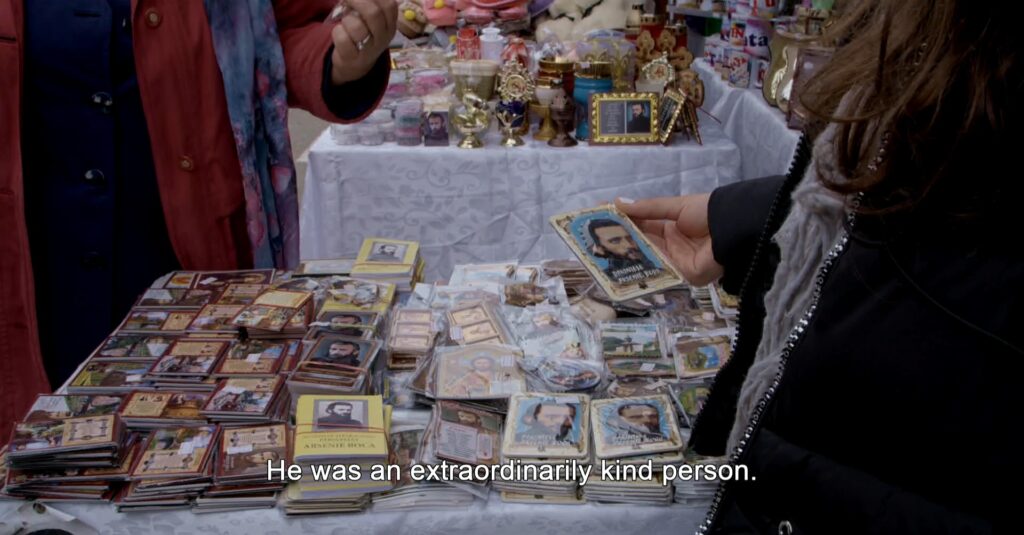

Despite constant scrutiny, Boca’s reputation for miracles and prophecies grew. Legend claims he personally warned Nicolae Ceauçescu of impending danger. The priest himself didn’t live long enough to witness the unfolding of the foretold events––he died three weeks before Romania’s violent 1989 revolution, a timing that only fueled the mythos surrounding him. In 2019, the Holy Sinod of the Romanian Orthodox Church approved his canonization, further solidifying his status as a national spiritual figure. The Prislop Monastery, the place of his burial, has since become one of Romania’s most popular pilgrimage sites. His image adorns souvenirs and tattoos, his legacy is examined on the radio and television, while his quotes circulate online as spiritual guidance. Boca is embedded deeply in the Romanian national consciousness as both a martyr and a genius.

Alexandru Solomon’s documentary Arsenie. An Amazing Afterlife (Arsenie. Viața de apoi (2023) moves beyond Boca as an individual to explore the wider phenomenon of his posthumous popularity. This approach is evident from the opening scenes, which highlight the recent activities of the Romanian Orthodox Church. With its unwavering proclamations on how to live and its ostentatious public rituals, the Church seems to leave little room for dissent or critical engagement. Solomon disrupts this seemingly straightforward depiction with a metacinematic twist in which the documentary footage transforms into a video playing on a tablet in the director’s hands. This Brechtian intervention signals the constructed character of the represented reality, as if Solomon suggests “look, this is reality, it is not a film!” (even though the material is absolutely a part of Solomon’s film). This is what reveals Father Arsenie as a metonym for broader social dynamics––or, in a more cynical interpretation––merely a mascot for them.

Solomon’s treatment can be seen as engaging with what literary theory recognizes as “aesthetics of reception,” the examination of responses to a phenomenon in specific historical and personal contexts, not in isolation. Known for probing Eastern Europe’s social realities, especially the beliefs and promises of previous regimes (The Great Communist Bank Robbery, Cold Waves, Kapitalism: Our Improved Formula, and Tarzan’s Testicles), Solomon now investigates the “Father Arsenie Boca Effect” by focusing on his devotees. Through interviews and observations, he subtly critiques the escapist tendencies of pilgrims. Without overt didacticism or condemnation, satire is employed to highlight the absurdities surrounding Boca’s legacy.

The film juxtaposes two layers of storytelling: the pilgrims’ journey and the staging of an amateur hagiographic play about Boca’s life. This dual narrative structure is brilliantly realized in scenes where interviews take place in the foreground, while the theatrical performance unfolds in the background. The dynamic interplay between the two underscores the ways in which Boca’s story is shaped, retold, and mythologized. Events happen against the backdrop of an amateur hagiographic drama, figuratively as well as literally. The dynamic interplay underscores the ways in which Boca’s story is reshaped, retold, and disseminated.

Solomon situates Boca’s cult within the broader context of a conservative turn internationally, which takes on unique forms in post-socialist societies. In these contexts, the resurgence of religious devotion and nationalism acts as a counterbalance to decades of state-enforced collectivism and materialist ideology. The popularity of Prislop has parallels in other pilgrimage sites in the ex-Yugoslav region, such as Međugorje in Bosnia and Herzegovina or Ostrog in Montenegro. Solomon captures the incongruities of these spiritual destinations, where sacred values often coexist uneasily with the profane realities of mass tourism. At Prislop, pilgrims browse through thousands of commodified objects–but emblazoned with holy imagery.

National heroes rarely emerge by chance. Their controversy stems from their potential to indebt the community in polarizing ways, embodying deep societal divisions. Similarly to Boca, Croatia’s Archbishop Aloysius Stepinac was accused of supporting and advancing in a fascist regime, at the very least failing to oppose it decisively. In fractured societies, such figures become rallying points for identity formation, either as revered saints or contentious symbols of past wrongs.

Discussions of Boca inevitably lead to reflections on post-socialist Romania. What has privatization brought to the country? How was it implemented? Ordinary citizens, preoccupied with their daily struggles, often lack the knowledge to fully comprehend the larger forces shaping their lives. This gap in understanding is where figures like Father Arsenie step in, providing a source of solace or explanation in an increasingly complex world. A retired accountant recounts how deliberate misconduct during the early democratic years devalued entire industries, making such stories sound less like conspiracy theories and more like plausible truths of transitional economies.

While rooted in a specifically Romanian context, Arsenie. An Amazing Afterlife has international resonance. The symbolic processes surrounding Boca’s cult mobilize emotions and reveal patterns that transcend national borders. Solomon’s film is rich in cultural specificity yet poses questions relevant to the liberal world as a whole–how do citizens make informed decisions, where do they find purpose, and do they define their responsibilities.